Synopsis

Press play to watch an introduction by director

Rob Melrose

Scene One

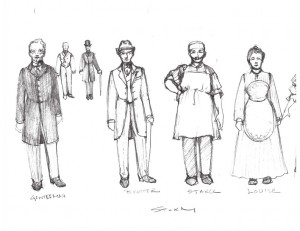

When the play opens, the audience is looking at the façade of a yellow, multi-story apartment complex. The windows of the second floor are hidden with backlit, red shades. While Mr. Starck, a confectioner, sits outside on the sidewalk, another elderly gentleman eats inside in the dining room. He tells his brother, a consul, that he’ll join him outside in a minute. The consul leaves to converse with the confectioner, who describes the house as abnormally quiet because the tenants of the house keep to themselves. Mr. Starck tells the brother that he has never seen the couple who lives on the second floor above the gentleman leave once; the brother imagines that the red shades of the lamps in their apartment “look like stage curtains behind which someone’s rehearsing bloody dramas.” The confectioner mentions that he has “seen a whole crowd up there [on the second floor], but only later, at night” before leaving.

When the gentleman joins his brother outside, he reveals that he stays inside his home every evening because he feels “immobilized” and “bound to [his] apartment by memories,” and that he has never gone to the countryside during the ten years that he has lived in the hushed town. Although the gentleman knows very little about his secretive neighbors, he claims that he and the confectioner know the most about the apartments because they are the eldest residents. Suddenly, a woman wearing a black dress peeps out the window that belongs to the gentleman’s upstairs neighbors. Then, a bald man dressed in evening wear deposits a thick stack of letters into the mailbox in front of the apartments. The gentleman conjectures that it must have been his upstairs neighbor.

The brothers’ topic of conversation turns to Louise, the gentleman’s maid. When the consul asks whether the gentleman has considered marrying her, he says “no.” He reminds his brother that his last marriage ended badly five years ago. In fact, the consul thinks that the gentleman’s ex-wife “murdered” his honor when she left him. When the gentleman asserts that he has put the unhappy affair behind him, his brother skeptically observes that he thinks the gentleman is “living a willful lie.”

As the brothers leave for their evening stroll, Louise and Mr. Starck converse about Louise’s “quiet, beautiful life” and the close, respectful relationship between the brothers. Agnes, Mr. Starck’s daughter, tries to sneak out of the house without him noticing. When he does notice, she quickly explains that she is “just going out for a little walk.” After Agnes leaves, the confectioner and Louise’s discussion returns to the gentleman. Louise conjectures that “he doesn’t grieve [the loss of his loved ones], doesn’t miss them either since he doesn’t wish for them back. But he lives with them in his memory where he only accepts what’s beautiful.” Mr. Starck adds that the gentleman does worry about his daughter’s future, however, and shares a rumor he heard about the gentleman’s ex-wife refusing any kind of financial support at first before demanding “several thousand” via a lawyer several years later.

A delivery man arrives with a basket of wine bottles addressed to a Mr. Fischer, whom the confectioner guesses must be the upstairs neighbors. He and Louise reflect on the fact that although they have never seen the neighbors because “they always go out the back way,” they have certainly heard their “doors slam [and] corks pop.” As Mr. Starck leaves to continue making jam in his confectioner’s shop, the consul comes back from his walk without his brother who had “stopped to make a telephone call.” The consul finds a postcard on the ground addressed to the Fischers from the Boston Club, which sounds dubious to him. He then hesitantly asks Louise whether his brother has ever spoken of the past with Louise. “Never to me,” she replies quickly, and then leaves before the consul has a chance to ask her anything else.

The confectioner emerges sweating from his sweltering kitchen and joins the consul outside. They hear a long, piercing cry from the upstairs neighbors’ apartment, which causes the confectioner to wonder — only somewhat sarcastically — whether their neighbors are “killing one another.” When another scream radiates from the stairwell, the shaken confectioner, wanting “nothing to do with this,” retreats back into his shop.

Subsequently, Gerda, the gentleman’s ex-wife and the consul’s former sister-in-law, arrives looking distraught. She reveals that she, her daughter, and her husband, a singer turned conman, are the tenants of the ominous apartment upstairs which her abusive husband has converted into a gambling house. Ever loyal to his brother, the consul demands to know why Gerda robbed the gentleman of his honor. Gerda holds that her ex-husband was “too old” and that he had abandoned her. Gerda refuses to apologize because she is convinced that “if things are made right for him it will be at [her] cost.” Perplexed by Gerda’s “strange” thinking, the consul foregoes trying to convince her to apologize and instead attempts to persuade her to save the daughter she had with the gentleman. Gerda and the consul hide in the shadows as the gentleman enters the house and sits in the dining room. The consul points out to Gerda how his brother left his home arranged to her tastes long after she left him, and that he is still in love with the memory of her — in fact, he keeps a portrait of her and their daughter above the mantel. When a bolt of lightning suddenly illuminates Gerda and the consul, the gentleman sees them both, and Gerda hides. The gentleman dismisses the image of his ex-wife as a figment of his imagination and returns to the table. Gerda finally agrees to return to her apartment with the consul to try to save her child as the gentleman calls out to his brother to join him for a game of chess.

Scene Two

The second scene commences inside the dining room as the gentleman asks Louise where his brother, the consul, went. The din upstairs has intensified so much that the chandelier shakes as Louise joins the gentleman for a game of chess. Louise encourages her employer to move soon because “it’s not good to sit so long with old memories,” but the gentleman is convinced that “all memories are beautiful. Mr. Starck, the confectioner, arrives bearing pastries. The gentleman realizes that it has been ten years since Mr. Starck has been inside his home, the last time being when he delivered the gentleman’s wedding cake. The gentleman reasons that his solitude is serne:

“[It is] peaceful… No love, no friends, only a little company in the midst of solitude. People become people, without claims on your feelings or sympathies. One [person] gets loose like an old tooth, and then falls out without pain or loss… By keeping things neutral with others, one develops a certain distance, and with distance things go better.”

As Louise busies herself with the laundry and Mr. Starck returns to his shop, the gentleman grows increasingly anxious about the unknown whereabouts of his brother. Three times the gentleman hears something and mistakenly thinks it is his brother. The first time, it is the postman delivering another postcard from the Boston Club addressed to Mr. Fischer; the gentleman tears it up in anger. The second time, it is merely the iceman. The third time, he only hears a bit of Chopin’s “Fantasie Impromptu, Opus 66” being played in the apartment above. His brother finally returns, using the vague excuse that he “had something [he] had to take care of.” The brothers begin to wax philosophical, and the gentleman states that he has never been able to separate the memories of his ex-wife from the ones of his daughter, which he cites as his reason for refraining to seek custody of the latter. The consul asks him whether he ever considered “the possibility of a stepfather… A stepfather who mistreated, perhaps even degraded [his] daughter.” Without addressing the question, the gentleman thinks he hears “the patter of little feet” and begins to gloomily reminisce about his daughter. He adds that, “these past few days I’ve been dreaming every night about little Anne-Charlotte… I see her in danger, unknown, lost, without a name. And just before I fall asleep, my hearing gets unbelievably sharp, and I hear her small steps. Once I heard her voice…” When the consul asks him how he imagines he would react, he recoils at the possibility of not recognizing his own offspring and firmly decides that he would rather only have the sweet memories of her as a young child.

The gentleman leaves his brother to write a letter just before Gerda arrives to beg for his help. Her current husband, Fischer, has run away, holding her daughter hostage in order to provoke Gerda into following him and to train her as a ballet dancer. She examines the room and sees that her ex-husband really has preserved his house; it looks the same as the day Gerda left five years before. The consul leaves Gerda alone, and she begins to panic, fearing that asking for her ex-husband’s help was too presumptuous. Her ex-husband walks by, sees her, but mistakes her for Louise due to his nearsightedness. He makes a phone call to his mother; when he hangs up, he recognizes Gerda and nearly collapses from the shock. Gerda pretends that all is well, and answers the gentleman’s stammered questions about her life politely. He tells her that he would rather not see their daughter as he could not deal with the emotional stress involved. Finally confronting his painful memories, the gentleman tells Gerda that he only married her to save her from the embarrassment of having a child out of wedlock. He disparages her for acting like she was planning to murder him:

“As soon as I made an enemy, he became your friend. Which led me to say: ‘True, there’s no need to hate your enemies, but why do you have to love mine?’ Anyway, when I saw where we stood, I began to pack up, but I wanted a living witness that you were playing with lies, and so I waited for the birth of the child.”

The gentleman accuses her of reshaping his friends into his enemies, convincing his brother into betraying him, and instigating rumors about the legitimacy of their daughter’s birth, therefore forever staining her reputation. The gentleman even admits that he met his daughter once on the stairs of the apartment, and she thought he was her uncle. The experience was so horrible for him that he told no one and tried to erase the memory of it completely. Gerda offers to try to make things right, but her ex-husband scorns her the same way he claims she used to scorn him. It becomes apparent that Gerda is jealous of the gentleman’s relationship with Louise; he condescendingly assures her that he has resigned himself to solitude. The telephone rings, bringing word that Fischer has run off with Agnes, Mr. Starck’s eighteen-year-old daughter. Gerda finally tells the gentleman that Fischer took their daughter with him; the brothers agree to help her.

As Gerda and the consul shield themselves against the rain and leave for the police station, the gentleman sits down for a game of chess with Louise instead of accompanying them. He asks her whether she knew much about Agnes or about the upstairs neighbors; when she says no, he accuses her of being evasive, warning her that “an adopted deafness can be taken too far and can be dangerous.” The scene ends with Louise agreeing not to ask the gentleman anything about the unfolding events.

Scene Three

As the third scene begins after the rainstorm, we find ourselves looking at the same façade of the apartment complex as in the first scene — this time, though, the red shades on the second floor have been pulled up. Outside, the confectioner informs the gentleman that he does not own a telephone in order to avoid messages. The gentleman supports Mr. Starck’s reasoning, adding that “I always feel a little twinge in my heart when it rings — one never knows what one will hear… and I want to be left in peace… peace above all.” Just then, the gentleman’s own telephone rings. Louise answers it and informs her employer that his ex-wife wants to speak to him. He refuses to talk to her or to answer the phone at all to avoid bad news — he argues that “Things sort themselves out better if you don’t entangle yourself by getting involved.”

Agnes Starck returns, looking disheveled. Her father, the confectioner, accepts her excuse that she had been out walking;.Louise and the gentleman wonder whether Mr. Starck knows that she had actually been with Fischer as both Agnes and Mr. Starck exit. Louise tries to convince the gentleman to help Gerda for the sake of their daughter; he adamantly refuses because his daughter “destroyed [his] beautiful memories” by calling him her uncle and Fischer her father when they met on the stairs.

The consul approaches after a long night of trying to help his brother’s ex-wife; the gentleman is wary of him because he thinks his brother has betrayed him “whenever he came near [Gerda.]” He begins to tell the gentleman of what had happened during the night. The consul had accompanied Gerda to the train station, where they saw Fischer with Agnes and the daughter. When the daughter saw that Fischer had purchased third-class tickets, “she threw them in his face [and] Gerda hurried up, took the child, and disappeared in the crowd.” Fischer then told the consul his side of the story (the details of which the consul does not explain), which caused the consul to sympathize with him. The gentleman is enraged that his brother is siding with his enemy. He accuses the consul of “only [believing] lies, and all this because — you were in love with Gerda.” The consul concludes his story by telling the gentleman that Fischer left for good; Louise gets a phone call confirming that Gerda and the daughter have moved to the countryside. The gentleman instructs Louise to “close the windows [of Fischer’s second-story apartment] and pull down the shades, so the memories will lie down and sleep in peace.” As the play ends, the gentleman resolves to move away from the house to escape his bitter memories once and for all.