Strindberg’s Breakthrough as an Artist

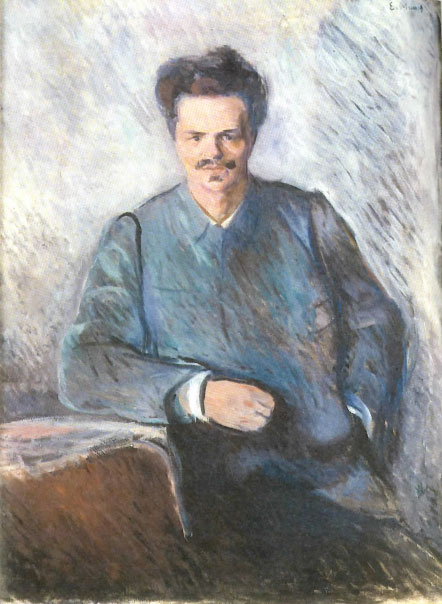

In 1879, August Strindberg was the new “it” author in Scandinavia. Having dabbled in playwriting and painting and having worked for some time as an assistant librarian at the Royal Library in Stockholm, he was known of by some but had yet to make the first of many splashes in Swedish literary circles. That breakthrough would come with the novel The Red Room (Röda rummet) in 1879. A no holds barred critique of the Stockholm bohemian artist community; many hailed the novel as the first modern novel written in Swedish. More importantly (for Strindberg’s career, perhaps) it earned high praise from Georg Brandes[KL1], the Danish critic whose 1871 lecture series “Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature” is responsible for bringing the tenants of Modernism[KL2] (in particular Realism[KL3] and Naturalism[KL4] ) to the north and for inspiring the strident social realism of artists like JP Jacobsen[KL5] and Henrik Ibsen[KL6]. An endorsement by Brandes opened up doors and for Strindberg, who was only thirty years old at the time of the novel’s publication, Brandes’ support would thrust his work (and by extension, his life) into public view in a way that even a royal grant for his 1871 historical drama The Outlaw (Den fredlöse), couldn’t do.

That is not to say, of course, that Strindberg would have a charmed literary career post Red Room. He wouldn’t – in fact this was just the beginning of a troubled career (and even more troubled personal life) that would end with his death on May 14, 1912 at only age sixty-three, to stomach cancer. It is this dramatic life and dramatic career, however, that would lead him to create some of the most enduring work of late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and which would find him, in his last years, experimenting with achieving expressionistic visions onstage, and pioneering what would become the theatrical avant-garde[KL7] through his collaborations with August Falck and the members of The Intimate Theater (Intiman) in Stockholm.

Blasphemy

Inspired by the work of the great French Naturalist Émile Zola[KL8]early in his career, Strindberg combined Brandes call for Social Realism with Zola’s pioneering Naturalism and fervently attacked most every notable institution in nineteenth century Europe. Unlike Ibsen, however, whose drawing room dramas attacked bourgeois hypocrisy and restrictive social mores and which found support in the burgeoning women’s movement and socialist politics, Strindberg’s ultra-radical views regarding gender roles and top-down culture often got him into trouble. Labeled a misogynist, his claims that the women’s movement was anti-natural and that peasant life, with its equal distribution of household duties along gender lines, was the model of “natural” human society[KL9], were met with disdain by progressive thinkers of the day. In 1884 he was forced to return to Sweden (he and his first wife were living in France with their three small children at the time) to face trial for a charge of blasphemy, related to a passage in a short story The Reward of Virtue in which he referred to Jesus Christ as a “great agitator” who was “done to death” and in which he claims that the body and blood of Christ offered during communion were simply cheap wine and wafers bought in bulk from the local merchants. While he was acquitted of the blasphemy charge, the publication of this short story collection Getting Married (Giftas) and the subsequent fallout was the beginning of the end of his first marriage to actress and former baroness Siri von Essen. According to their oldest daughter, Karin, in a book written about her parents rocky relationship and her father’s supposed mental illness, Siri was humiliated by the collection, which painted marriage (and wives in particular) in a negative light and, which she believed implied publically that she was a wife of this order.

Strindberg viewed his acquittal at this trial as a victory over his many and varied opponents and returned to France feeling triumphant – a feeling which would not last long. He would spend the next few years traveling, living in various places within France, Switzerland and eventually Copenhagen, just across the Öresund straight from Sweden, as his relationship with Siri continued to deteriorate. Strindberg’s self-imposed exile had begun in 1882 after the publication of The Swedish People (Svenska Folket); a 1000 year history of the Swedish people and Swedish culture, which garnered some posthumous support but earned him a number of enemies in Sweden at the time of its publication. He refused to return to Sweden (excepting for his trial) for seven years. After several years working in the novel and short story formats (including a second, more acerbic installment of Getting Married (Giftas II) in 1886) he turned his attention back to drama with his 1886 play Mauraders (Marodörer) a minor work that is rarely read now. His follow-up to Marauders in 1887, The Father (Fadern) is often viewed as the first of his major theatrical accomplishments, as his newly formed fascination with Zola allowed him to experiment with Naturalism and in so doing, hit his artistic stride.

Successes with Naturalism

The Father, which tells the story of Adolf, a Captain in the Swedish military as he battles with his wife Laura over control of their daughter’s future, is one of Strindberg’s most frequently produced plays. He believed, when he wrote it, that he had succeeded in writing the “perfect Naturalist drama” and sent a copy (in his own French translation) to Zola. Despite a generally favorable response from Zola, the French master did not share Strindberg’s conviction that this play was “the perfect” Naturalist drama, a fault that Strindberg would attempt to remedy with this follow-up piece Miss Julie (Fröken Julie). Like The Father, Miss Julie is one of Strindberg’s most frequently produced dramas. The play again revisits some of the playwright’s long-held views of women and gender roles as it depicts the inevitable (in Strindberg’s mind) destruction of a young woman who defies “natural” gender – both in upbringing and behavior.

Despite this early commitment to Naturalism, these relatively early masterworks feature themes and motifs that will reoccur even after he had abandoned Naturalism as an outmoded form. Besides the theme of gender conflict (which actually becomes more tempered as he ages), they both address the idea of destruction and rebirth, human vampirism and hidden truth. In particular, The Father is built on the troubling concept that paternity (pre-DNA testing) can never be proved – an idea that is repeated in Burned House when the Stranger responds to the question of paternity of the student with the line “No-o-o. But since fatherhood can never be denied, I’m like a stepfather.” Though rhetorically, the concept has been reversed – here it is a question of paternity being denied, rather than proven – it reflects a continued preoccupation with the same masculine insecurity. Despite the significant evolution of his style in the time between the publication of The Father and Burned House, Strindberg continues to struggle with the same questions that troubled him twenty years before.

The end of one marriage… and the next.

In 1889, while still living in Copenhagen, he attempted to open his own small theater, The Scandinavian Experimental Theater, with his estranged wife Siri as the theater’s director. In a progression of events that can be read as inevitable, considering the Strindberg’s volatile relationship, the theater failed after only a few short months. Strindberg’s dream of a theater company where he could stage his own experimental works would not reach fruition until just five years before his death when he would join forces with actor August Falck in the foundation of The Intimate Theater (Intima Teatern)[KL10] in Stockholm.

After the failed attempt at running The Scandinavian Experimental Theater in Copenhagen, Strindberg and Siri separated for good, though their divorce would not be final until 1891. After a brief return to Sweden and the Stockholm archipelago, he returned to the continent where he met, married, had a child with and divorced second wife Frida Uhl in less than three years. Frida was twenty-three years his junior and the daughter of Friedrich Uhl, editor of the respected Vienna newspaper Wiener Zeitung[KL11]. Young and ambitious, Frida took charge of Strindberg’s floundering financial concerns and made herself into his de facto literary manager. Using her contacts in London, she tried to bring Strindberg and his works to an English speaking audience, but the combination of his resentment toward her for attempting to play too active a role in male-dominated financial and business matters and an intense dislike for London led to an unhappy return to Austria. This unpleasantness was further complicated by the fact that the British business trip was also to double as the new couple’s honeymoon – insuring that marriage number two would start off poorly (and end quickly).

Inferno

From 1896 to 1899 he lived between Paris, Lund, in the south of Sweden and Vienna. It was during these years when he entered into what he would later describe as his “Inferno Crisis,” a period of mental instability marked by paranoid episodes, experimentation with alchemy, occultism and severe depression. Having moved away from Naturalism, this period also marks a shift in his writing style towards a version of early Expressionism[KL12] with distinct influences from the Symbolist[KL13] movement. While living in Lund, he wrote and later published his factually enhanced work From an Occult Diary. The diary, which is written in the first person and reads like selections from his own diary, is in actuality a combination of fact and fiction. While it cannot be read as autobiography, it does offer insights into Strindberg’s state of mind during this period and develops some of the themes that he had previously addressed and those which he would later address in his other writings.

The Return to Stockholm

In 1899, Strindberg finally returned to Stockholm, where he would live until his death thirteen years later. While he continued to work in various formats, he once again returned to drama as a source of inspiration and an outlet for experimentation. These works, referred to by scholars as “post-Inferno”, wholly forsake the Naturalism that he had embraced so enthusiastically just twenty years prior in favor of wide ranging experimentation. After more than five years of writing only sporadically, he became incredibly prolific, incredibly quickly. In only three years, he published seventeen times, including twelve plays. Among those is the To Damascus series, which combines the Biblical tale of the conversion of Paul [[KL14] with elements of the medieval [KL15] and the dreamlike, symbolic elements that would characterize many of his later works. Strindberg scholar Gunnar Ollén, describes the series as “a drama of struggle, the story of a restless, arduous pilgrimage through the chimeras of the world towards the border beyond which eternity stretches in solemn peace, symbolized in the drama by a mountain, the peaks of which reach high above the clouds [1].”

A Third Wife

In 1901, the 51 year-old Strindberg married the 22 year-old actress Harriet Bosse [KL16]. Like his two previous marriages, this too was destined to be short lived and full of sturm und drang [KL17]. Though he often referred to her as his muse and wrote several roles with her in mind, their May-December relationship could not survive Strindberg’s ever-changing moods and incessant jealousy. They were separated before they had been married a year and were officially divorced in 1904. In spite of their whirlwind marriage and divorce, they continued to correspond and Harriet continued to act in productions of Strindberg’s plays – most notably originating the role of Indra’s Daughter (a role written for her) in A Dream Play when it premiered at The Swedish Theater in Stockholm in 1907.

The Intimate Theater

In 1907, Strindberg joined forces with August Falck[KL18] to create The Intimate Theater (Intima Teatern) in Stockholm, which would finally give Strindberg a venue where he could stage his own works. Strindberg and Falck had met in 1906 when the young actor requested the playwright’s permission to bring his production of Miss Julie to Stockholm. Biographer Michael Meyer retells Falck’s account of their curious first meeting when Strindberg greeted the young man, whom he had invited to his home to discuss the production, with several moments of silent scrutiny followed by an enthusiastic “Your name is August! Your name is Falck! Welcome!” According to Falck it took him some time to decode this strange greeting but finally discovered that the aging, spiritual Strindberg saw the combination of their shared first name and the young man’s shared surname with the protagonist of his breakthrough novel The Red Room (Arvid Falk), as a propitious sign[2]. Indeed, the two would have a fruitful working relationship, however short, as the new theater would host 1500 performances both at their location in Stockholm as well on tour in just under three years. Additionally, the opportunity to finally work closely with performers who were staging his plays as they prepared them for performance, allowed Strindberg a chance to exercise some of his philosophies about the value and function of theatrical performance. Rather than giving notes to his actors in closed rehearsals as present-day playwrights and directors might, Strindberg composed a series of memorandums to the performers, explaining his thoughts and intentions. Like the prefaces he composed to accompany his earlier, published works, these letters offer fascinating insight into the mind of the author an have been collected and published as Open Letters to the Intimate Theater.

The Chamber Plays

In preparation for the opening of the theater, he composed the four plays Storm, The Burned House, The Ghost Sonata and The Pelican; calling them “Chamber Plays” (“kammarspel”) after Max Reinhardt’s [KL19] experimental kammerspiele theater at Deutches Theater in Berlin. Falck opened the theater with a performance of The Pelican on November 26, 1907 to horrible reviews, which, according to Meyer, inspired him to revive the production ofMiss Julie for a short run before attempting to perform The Burned House a week and a half later, on December 5th, again, to discouraging reviews. Storm, which premiered on December 30th, went over moderately better with critics and ran for almost a month, but any good will that the young company had earned with this production was destroyed with the premiere of The Ghost Sonata on January 21, 1908. Though Ghost Sonata is now thought of as one of Strindberg’s greatest works and is certainly the most popular of the chamber plays, it was a radically avant-garde piece for the Stockholm critics (and audiences) of the day and only managed twelve performances before it was replaced by Playing with Fire (Leka med elden)and The Bond (Bandet), which he had written in 1893. Though these two also failed to impress the critics, their next production Pariah (Paria), from 1889, did well and temporarily revived the floundering theater. The Chamber Plays would not see successful stagings until Reinhardt produced them in Berlin in 1916. The Austrian, who is responsible for several renowned stagings of the works of both Strindberg and Ibsen, approached these pieces with an unabashed commitment to the Expressionistic and Symbolist elements that they deserve, which likely made the difference between their success in Berlin and their failure in Stockholm, though admittedly, a wartime Berlin provided audiences that were much more receptive to experimentation and expression than the conservative Stockholm audiences of the previous decade.

Fanny Faulkner

Among the company of actors at the Intimate was eighteen-year-old Fanny Falkner[KL20]. A close relationship quickly developed between the girl (who was eleven years younger than Strindberg’s oldest daughter Karin) and the playwright who moved into an apartment in the same building as the Falkner family in 1908. Strindberg and Fanny visited everyday and the young actress was kept on at the Intimate at the insistence of Strindberg himself, as Falck, who was in charge the theater’s actors, did not think much of her acting abilities. According to a book published by Falkner in 1921, she had agreed to be the fourth wife of Strindberg but changed her mind and moved to Copenhagen before any wedding could take place.

One Last Scandal

As with most of his relationships, the working relationship with August Falck eventually soured and in 1910, after three years of financial and artistic ups and downs, the Intimate Theater closed. It had been a fruitful three years, however, with the theater hosting the Swedish premieres of at least ten of Strindberg’s plays and performances of at least five others as well as providing an opportunity for the playwright to share his thoughts about the performance of his works in the series of letters, Open Letters to the Intimate Theater, mentioned above.

The last years of Strindberg’s life were marked by one final public scandal; a two-year series of attacks and counter attacks between the author and his opponents in various Swedish newspapers that would come to be known as “The Strindberg Feud.” It began on April 29, 1910, with the publication of his article “Pharaoh-worship” (Faraon-dyrkan) in the in the leftist newspaper Afton-Tidningen, which, perhaps not so incidentally, had its editorial office in the same building where Strindberg lived. While, the article criticizes the seventeenth-century Swedish King Karl XII[KL21], Strindberg’s attack was primarily leveled at the contemporary social and political movement that promoted the warrior king as a national hero, despite the overwhelming evidence that he was a tyrant who misused his power at the expense of his people. This prompted an angry response from adherents of this conservative movement and sparked a two-year long debate that appeared in several newspapers in which Strindberg attacked most of the Swedish establishment from the writers Verner von Heidenstam [KL22] and Oscar Levertin [KL23] to the Swedish Academy and the monarchy itself.

On January 22, 1912 – his last birthday- Strindberg was awarded an anti-Nobel prize by a group of workers and students who had started a public collection to support the author. After having been denied the prize by his opponents in the Swedish Academy for seven years, he was honored by a crowd of thousands who gathered under his balcony at 85 Drottninggatan in Stockholm. Four months later, after battling pneumonia and stomach cancer, Strindberg died on May 14, 1912.

By Kimberly La Palm

PhD student

Scandinavian Section

University of California, Los Angeles

Sources:

Meyer, Michael Leverson. Strindberg: A Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. Print. Oxford lives.

Strindberg, August. Samlade Skrifter; Naturalistiska Sorgespel. Stockholm: A. Bonnier, 1920. Print.

- (February 4, 1842 – February 19, 1927) Danish literary critic responsible for promoting the “modern Breakthrough” in Nordic literature.↵

- An artistic movement beginning largely with an interest in Realism which came to encompass several different movements within Western literature from the mid 1800s to WWI.↵

- An artistic movement that focused on using artistic mediums to represent the reality of the viewer. This was a drastic change from the art of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries with focused largely on tragedy and melodrama within the privileged classes.↵

- An offshoot of Realism that attempted to represent reality in all of its gritty and often unpleasant detail. Inspired by Emile Zola, the French playwright and novelist who started the movement, Strindberg looked at his Naturalist works as akin to science experiments on the page, in which the conclusion was the inevitable result of natural law at work.↵

- (April 7,1847 – April 30, 1885) Danish pet and novelist.↵

- (March 20, 1828 – May 23, 1906) Norwegian playwright and poet.↵

- French “vanguard” – referring to works that are at the forefront of a movement.↵

- (April 2, 1840 – September 29, 1902) French playwright and novelist.↵

- Preface to Giftas↵

- http://www.strindbergsintimateater.se/↵

- Established in 1703, the Viennese Newspaper has been one of the most respected news sources in Europe for 300 years. As of 1812, it has been the official newspaper of the Austrian government.↵

- A European artistic movement that began at the end of the nineteenth century and remained influential well into the twentieth century. The movement was concerned with representing the subjective experience of the artist/viewer and educing an emotional response. One of the most well-known Expressionists of the period who has enjoyed continued popularity is the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.↵

- A European artistic movement that began at the end of the nineteenth century and remained influential well into the twentieth century. The movement was a reaction to the Realism that had predominated earlier in the century and focused on the ephemeral and dreamlike.↵

- (Acts 9:1-31) In this Biblical tale, the Pharisee Saul, a particularly zealous persecutor of early Christians, is intercepted while on his way to the city of Damascus by a blinding light. He has a conversation with the voice of Christ from the heavens and is convinced to follow His teachings, eventually becoming the apostle Paul.↵

- A popular form of performance during late medieval period, morality plays often focused on the journey of the protagonist as he faced earthly obstacles which encouraged penitence for his past sins while also prompting a conversion to a more spiritual life.↵

- August Strindberg. The Road to Damascus (Kindle Locations 51-53).↵

- Strindberg met the young Norwegian actress while she was part of the company at The Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm.↵

- “storm and stress”↵

- A young Swedish actor who impressed Strindberg with his staging of Miss Julie.↵

- Meyer, Micheal. Strindberg: A Biography. (473)↵

- Legendary Austrian director renowned for his innovative productions while at Deutches Theater. Reinhardt relocated to the United States in the 1930s to escape the Nazi persecution of Jews and spent the rest of his life between Hollywood and New York City.↵

- A young Swedish actress and member of the company at Intimateatern.↵

- Karl XII, king of Sweden from 1697 to 1718. He is best known for his attempts to expand Sweden’s (and his own) power and wealth through a series of ill-planned and ill-executed wars which reduced his country to poverty and famine. He lived in exile in Turkey for much of his reign and according to legend, was shot to death by one of his own men while preparing to invade Christiania (Oslo).↵

- (July 6,1859 – May 20, 1940) Swedish poet and novelist.↵

- (July 17, 1862 – September 22, 1906) Swedish poet, critic and literary historian.↵