The Cutting Ball Theater’s Strindberg Cycle will be the first time all five of Strindberg’s Chamber plays will be produced in succession, but many celebrated artists have approached the plays in the last century.

Of Strindberg’s five Chamber Plays, The Ghost Sonata is the by far the most produced – Egil Tornqvist’s book The Ghost Sonata includes detailed accounts of numerous productions over the years. The play premiered 21 Jan, 1908, at the Intimate Theater, but its original run had only 12 performances. It was received poorly, and even Strindberg’s long-time friend Anna Branting hoped Strindberg was not “pulling the Stockholm public’s leg.” After it’s unsuccessful opening, The Ghost Sonata drifted into obscurity until the play was remounted by the German director Max Reinhardt in 1916. Reinhardt’s production, arguably, was the first to demonstrate the symbolic significance of The Ghost Sonata. Notes on the production indicate that he focused on the visceral and aural aspects of the play, playing special attention to lighting, sound effects, and the physicalities of actors to craft a heightened, melodramatic interpretation of Strindberg’s work.

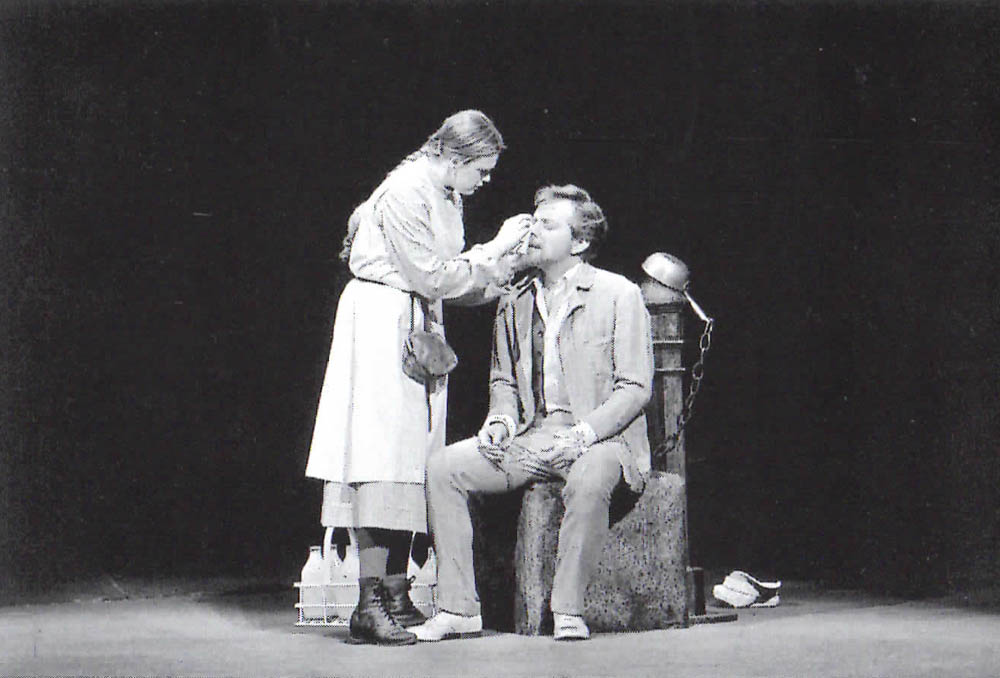

The Ghost Sonata did not return to Sweden until some years later, when it was staged by Olaf Molander, who would direct the play five times over his career. Molander’s staging was more subdued and realistic – produced on smaller stage, with gray-toned costumes. The celebrated director Ingmar Bergman, who would direct seven productions of The Ghost Sonata, first tackled the play in 1941 in an attempt he later would describe as only partially successful. After seeing Molander’s more realistic approach to The Ghost Sonata, Bergman’s drew heavily from his style in his second production. In this remounting, Bergman used similar used visual cues to stress that the audience was watching a dream play. The size of his stage was shortened and Bergman had a neutral gray curtain installed and side-lit the actors. Bergman’s second production ended using a ‘tableau vivant’ of the Student, sitting tenderly next to the Young Lady in what Egil Tornqvist calls an “inverted pieta, with the student as Madonna, offering compassion for all of mankind.”

Bergman varied even more from Strindberg’s original text in his 3rd, 1973 production of The Ghost Sonata. He modified the entrances, exits, and stage directions throughout the play, and even infused a new story into the text: he paralleled the love stories of the Student and Young Lady with the Woman in Black and the Baron. The Cook’s costume stressed her lower-class status, representing the proletariat, to contrast with the upper class characters of the Student and Young Lady. Bergman also cast the same actress as the Young Lady and Mummy to draw a similarity between those two characters. Bergman’s third production of The Ghost Sonata used projections as its set, with projections of interiors on an entirely blank wall. Bergman used audiovisual effects to create a sense of claustrophobia, and visually engulf the audience in the characters’ mental journeys, but also providing a tangible representation of the dream world. He placed clocks and other sound effects around the seats of the theater, creating a teatrum mundi effect. In this production, the Mummy and the Colonel are reunited at the end of the play, and during the final tableau the student delivers his prayer to them as the couple gather tenderly around the Young Lady, joined by strong light from above.

Egil Tornqvist writes that “When Bergman staged his first Ghost Sonata, in 1941, he was 23 – the same age as the Student. When he staged his fourth version, in 2000, he was 81, the same age as the Old Man.” In his fourth production of The Ghost Sonata, Bergman stressed the student as the dreamer of the play, and indicated theatrum mund (Latin for “the world stage”) with grandfather clock to left and marble statue to right like the 3rd production. Bergman identified the theme of this production was “virginity lost,”—specifically “sick at the womb”. Young Lady was portrayed as such, and her dress was blood-stained at the crotch by the end of the play. Bergman’s fourth production was grim: all characters had some sort of physicalities indicating infirmity of a kind, such as bloody hands or an ear trumpet. Though Mummy and Colonel’s love story was present again, they were not united at the end, and the oppressed proletariat motif was stressed even more: both the Cook and Johansson were in lower-class clothing. Bergman had no Toten-Insel, no religion, no hope, no faith, and no light at the end—and this rendition had the best reception, praised as most coherent, “sonorous”, “somber,” and ‘a horror film [like] silent film’ ” (145).